Appendix 2: 9th Regiment of Cavalry, State of Iowa

Roster and Record of Iowa Troops In the Rebellion, Vol. 4

By Guy E. Logan

HISTORICAL SKETCH

NINTH REGIMENT IOWA VOLUNTEER CAVALRY

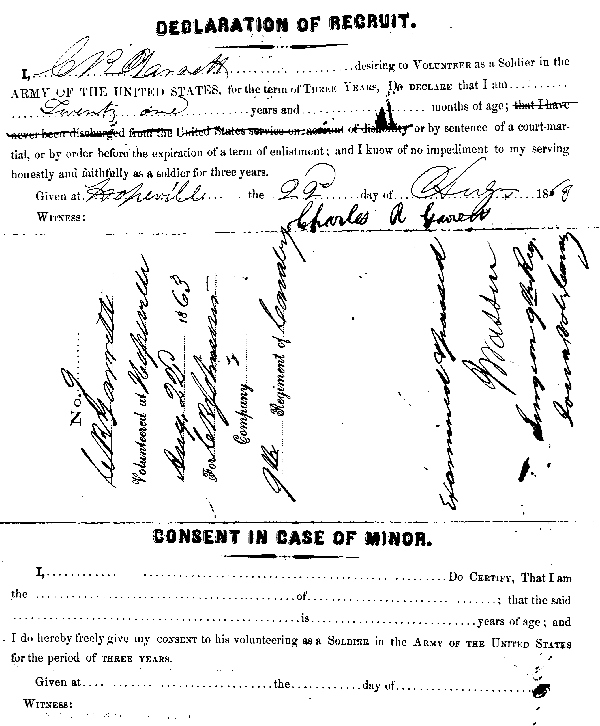

(Note: Garrett, Charles R. Company H. Age 21. Residence Hopeville, nativity Illinois. Enlisted Aug. 22, 1863. Mustered Aug. 22, 1863. Mustered out Feb. 3, 1866, Little Rock, Ark. See Company B, Eighteenth Infantry.)

The Ninth Regiment of Iowa Cavalry was organized under special order of the War Department, dated September 7, 1863. The twelve companies of which it was composed were ordered into quarters by the Governor of the State between the dates, August 15 and November 1, 1863. Davenport, Iowa, was designated in the order as the rendezvous of the regiment and, at that place, on November 30, 1863, the Enlisted men and officers of the twelve companies, together with the field and staff officers, were-mustered into the service of the United States by Lieutenant Colonel William N. Grier, of the Regular Army. The aggregate number of the regiment, at the date of muster in, was 1,185. Early additional enlistments brought the number up to the maximum strength of a cavalry regiment. A large number of men who desired to join the regiment had reported at the rendezvous after its ranks had been filled, and, as they could not be mustered into the Ninth Cavalry were assigned to other Iowa military organizations, then being raised, or to regiments already in the field. Lieutenant Colonel M. M. Trumbull, formerly of the Third Iowa Infantry, was chosen as the Colonel of the Ninth Cavalry, and no better choice could have been made. He had entered the service at the commencement of the war, as Captain of Company I, of the Third Infantry, and had won well-deserved promotion to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in that regiment. He was wounded at the battle of Shiloh, and subsequently commanded his old regiment, and won distinguished honor at the battle of Matamora. He resigned to accept the appointment of Assistant Adjutant General of Iowa, and was serving in that capacity when he was appointed Colonel of the Ninth Cavalry by Governor Kirkwood. Lieutenant Colonel John P. Knight was transferred from the Third Iowa Infantry, where he had served with honor as First Lieutenant and Captain, and Major Edgar T. Ensign had also served with equal honor as Captain in the Second Iowa Infantry. Indeed, the roster of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry reveals the fact that nearly all its field and staff, as well as its company officers, had seen service in other Iowa regiments, which was also true as to a large number of the Enlisted men. Nearly every county in the State was represented in the regiment. In the region of country to which its operations were confined, the regiment did not have the opportunity—which its gallant commander and his officers and men so ardently desired—to make a great battle record. However, as will be seen in this brief historical sketch of its operations, the Ninth Iowa Cavalry performed important and valuable service in the field to which it was assigned. Major and Brevet Colonel Edgar T. Ensign has furnished the Adjutant General of Iowa with a carefully detailed historical memoranda of the movements and operations of his regiment, embracing the entire period of its services To that officer the compiler is indebted for the main portion of the material which enables him to prepare the following condensed history. It will be his endeavor, while omitting some of the less important details, to include all the most essential points in the history of the regiment.

The first camp of the regiment was located near the city of Davenport, Iowa, and was called "Camp Roberts," but was subsequently changed to "Camp Kinsman," where comfortable barracks had been constructed. There, while awaiting its supply of horses, arms and other equipments, the men received preliminary instruction in their duties. Officers' schools were established, and the necessity for the enforcement of strict discipline was inculcated. On December 8, 1863, Colonel Trumbull received orders to move his regiment to St. Louis. At that time about 750 horses had been furnished. These, together with the camp equipage and other military stores, required several trains of cars for transportation, and it took three days to effect the transfer of the regiment from Davenport to St. Louis, where it arrived December 11th.

The first camp was located on the ground occupied by the rebel troops at the commencement of the war—old "Camp Jackson." There the regiment remained in tents, suffering much from the severity of the weather, until December 16th, when it was moved into quarters at Benton Barracks. In this great camp of instruction the men and officers of the regiment were subjected to a rigid and thorough training. The officers were required to pass an examination before a military board, and all, save one, passed the ordeal with credit. With reference to the one exception, Major Ensign says: "Owing to illness, and absence of other officers of his company, which threw on him all, or nearly all, their duties and responsibilities, he wasunable to spare the time requisite to master all the technicalities of cavalry tactics and army regulations." Nevertheless, he was a good officer, and his brother officers sympathized deeply with him, and felt that great injustice had been done in rejecting him. In the early days of the war, officers of volunteer regiments were not required to pass such rigid examination. They were hurried to the field, with but scant opportunity for instruction and learned their duties in the hard school of actual warfare. There is no doubt however, that the Ninth Iowa Cavalry was better prepared for effective service in the field, after its long period of training at Benton Barracks, than were any of the Iowa regiments which had preceded it, at this time they took the field. With much less careful instruction it might have performed all the duties subsequently required of it equally well, but, if it had been sent with the other Iowa cavalry regiments, where great battles were fought, the wisdom of the longer period of preparation would have had practical demonstration. The horses of the regiment were selected by a board of its own officers. They were fine animals. Each squadron was supplied with horses of a uniform color, and the regiment, when mounted and on parade, was greatly admired for its handsome appearance. At an inspection and review held by General Davidson, Chief of Cavalry, at Benton Barracks, he declared the Ninth Iowa the best mounted regiment he had seen during his nineteen years of service as a cavalry officer in the Regular Army.

During a portion of the time of its stay at Benton Barracks, details were made from the regiment for guards in the city of St. Louis, and detachments were sent to adjacent parts of Missouri and Illinois. Captain Flick's Company (B) was for several weeks stationed at Alton, Ill., as guards to a large number of rebel prisoners confined at that place. Captain Reed's Company (A) was employed in breaking up and dispersing secret rebel organizations in Southern Illinois and in capturing deserters from the Union Army.

On April 14, 1864, the First Battalion, under command of Major Ensign, moved by rail to Rolla, Mo., and went into camp there. A few days later, three companies of the Second Battalion, commanded by Major Drummond, joined the First Battalion at Rolla. On the 15th, two more companies arrived there, but were turned back without leaving the cars. It had been intended to concentrate the regiment at Rolla, from which place it was to march to Little Rock, Ark., but the country between those points having been found almost destitute of forage, it was not possible to move the regiment over it. The detachments were therefore ordered to return to St. Louis.

On April 19th the regiment moved to Jefferson Barracks, twelve miles south of St. Louis, where it went into camp in tents, just outside the Barracks. Early on the morning of tray 3d there came an order from Department Headquarters for the immediate detail of one hundred and fifty men and a field officer to report at once. The duty was assigned to Major Ensign, who, with detachments from three companies comprising the required number of men, rode rapidly into the city and reported to General Rosecrans. The Major was instructed to proceed with his command to Hannibal, Mo., by boat, and thence to march to Palmyra, to intercept the movement of the notorious guerrilla, Quantrill, and his band. That fiend in human form was moving towards Quincy, Ill., after perpetrating his horrid crime of murdering defenseless citizens at Lawrence, Kans. Major Ensign at once embarked his detachment on the steamer "Die Vernon" and proceeded to Hannibal, where he disembarked and marched rapidly to Palmyra, as directed. The guerrilla leader had been apprised of his approach, however, and made a rapid retreat. Following his usual method when pursued, he ordered his followers to separate, each man to take care of himself, with orders to reassemble at some designated rendezvous, at a remote distance. Major Ensign's command scouted the country for ten days, and succeeded in capturing a few of the guerrillas; but their leader and most of his band made good their escape. Having been relieved of the duty of hunting guerrillas, by a detachment of the Seventh Kansas Cavalry, on the 15th of May the Major returned with his detachment to the camp of the regiment at Jefferson Barracks. Upon his arrival, he found the regiment under orders to proceed to Devall's Bluff, Ark.

Major Drummond, with Companies B and E, embarked on the first boat, other detachments following until Clay 19th, when Colonel Trumbull embarked with the last detachment, and, on May 23d, the entire regiment was in camp at Devall's Bluff. Soon after the arrival of the first detachment, Major Drummond had a skirmish with a small force of the enemy, who rapidly retreated, carrying with them a number of Government animals which were being herded near the post. The Major succeeded in recovering some of the animals, but the rebels were well mounted, and, having a thorough knowledge of the country, succeeded in eluding their pursuers and escaped to the northward through the swamps. Devall's Bluff was an important post, being the depot from which all the supplies for the army commanded by General Steele were forwarded. The failure of General Banks' Red River Expedition had compelled General Steele to fall back to Little Rock, which was the headquarters of his army. The rebel forces under General Price constantly threatened the line of road over which the supplies for General Steele's army were conveyed, and which had to be heavily guarded.

On May 24, 1864, Colonel Trumbull was assigned to the command of the post at Devall's Bluff. He immediately proceeded to put the post in the best possible state of defense against the threatened attack of the enemy. Heavy fortifications were constructed, guarding the approaches by land, while the timber between the river and the line of works was cut down, and all obstructions removed from the river view, in order that the gunboats might take an important part in the anticipated battle. The garrison, under command of Colonel Trumbull, consisted of his own regiment (the Ninth Iowa Cavalry), the Third Michigan Cavalry, the Third United States Cavalry (of the Regular Army), a part of the Eighth Missouri Cavalry, the One Hundred and Twenty-sixth Illinois Infantry, one battery (the Second Missouri Artillery) and about one hundred negro troops. One of the fleet of gunboats was stationed in the river, off shore. As detachments of cavalry were constantly required for extensive scouting and guard duty, the defensive force was none too large, in view of the number of the rebel forces under General Price which were expected to engage in the attack.

Major Drummond, with four companies of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry was sent to the vicinity of West Point, on White River, to keep constant watch of the movements of the enemy and give timely warning of his advance. Major Ensign was placed in charge of the pickets and outposts. All the troops composing the garrison were worked incessantly. The constant arrival of transports, conveying supplies, unloading the stores and reloading them upon the cars for shipment to Little Rock, employed hundreds of men, while hundreds more were employed in strengthening the defenses, scouting in the surrounding country, on picket duty, guarding the line of communication with General Steele, and the performance of the regular camp duties, demanding the most constant activity and untiring energy upon the part of both officers and men.

On the 29th of May, Major Haddock returned with a detachment of four companies of the Ninth Cavalry from a scout down towards the mouth of the Arkansas River, and reported the assembling of a force of rebels, under the command of General Marmaduke, on the south side of the river. Major Drummond's detachment returned the next day, reporting a skirmish with a portion of the rebel force ommanded by General Shelby. Everything seemed to indicate a concentration of rebel troops for the purpose of attempting the capture of Devall's Bluff. A few days later, however, the enemy began aggressive movements against the less strongly defended outposts, rendering it necessary to send reinforcements from Devall's Bluff to the points most liable to be attacked.

On June 4th, Major Ensign was sent with Companies A, C, D and E of the Ninth, to the neighborhood of Searcy, on the Little Red River, with instructions to make a thorough scout in the vicinity of the road leading to the crossing of that stream and beyond it. He found that a considerable body of rebel troops, with some artillery under General Shelby, were located near Batesville. Captains Young and Dean, with their Companies (C and E), were sent still farther into the country, to the north and west, and returned without encountering the enemy, but with valuable information. Major Ensign lost two of his men— captured by the enemy— while on this scout.

On June 13th the detachment moved to Bayou Two Prairies, on the railroad between Devall's Bluff and Little Rock, and there found the balance of the Ninth Iowa, and the Eighth Missouri Cavalry, with Colonel WAX. F. Geiger, of the latter regiment, in command. A small stockade was the only defensive works there. Major Drummond, with his battalion (Companies B. E. H and L), was again sent northward, and, on the 29th of June, sent a dispatch from Austin, stating that he had located the rebel General Shelby on that side of the Little Red River. Colonel Trumbull, with what men of his regiment could be mounted, moved promptly to join Major Drummond, with the intention of attacking the rebel force, but found it to be only a portion of General Shelby's command, which scattered and fled upon the approach of Colonel Trumble's command. After thoroughly scouting the country, and discovering no further traces of the elusive enemy, Colonel Trumbull returned with his regiment to Bayou Two Prairies.

Major Ensign, commanding the advanced guard of the regiment, arrived at the bayou before the main part of the regiment reached it, and, by order of Colonel Geiger, joined the Eighth Missouri Cavalry, with one hundred men of the Ninth, and moved to Clarendon, thence to Devall's Bluff, there to participate in another expedition against the wily rebel leader, General Shelby. While engaging the attention of Colonel Trumbull, on the Little Red River, with a portion of his command, Shelby had crossed the White River with his main force, and, by a sudden march southward to Clarendon, succeeded in surprising and destroying a United States gunboat lying at that place. General E. A. Carr, then commanding the district of Little Rock, rapidly assembled a force of infantry, cavalry and artillery, and gave chase. In his retreat towards Augusta, General Shelby was hard pressed by his pursuers and fought them at every available point. Heavy skirmishing was performed by the cavalry, the rebels always retreating before the infantry could be brought forward. Major Ensign's detachment of the Ninth Iowa kept with the advance, and, by a hazardous night reconnaissance, located the enemy's position and won the special thanks of the General commanding. On the first day's advance from Clarendon, the little detachment had pushed forward with so much audacity that it came very near reaching and capturing the rebel General, who was giving his personal attention to the movements of his rear guard. Lieutenants Jacobs, of Company B, and Prole, of Company G, were especially commended for their gallant behavior. One of the guns, taken from the gunboat by the rebels, was recovered, and two field pieces were captured from the enemy. The loss of the detachment was two or three killed and a few wounded, but less than that inflicted upon the enemy. Several prisoners were taken by the detachment. Captain Young, in command of Companies C, I and F of the Ninth, joined Major Ensign at Clarendon on the return march. The two detachments then marched to Devall's Bluff, and found the remainder of the regiment in its old camp at that place. There was much sickness among the troops, caused by the intensely hot weather, impure water and miasma from the surrounding marshes. Many of the men died from the diseases thus engendered. There was also great scarcity of forage. The hot weather and lack of rain had caused the grass to become parched and destitute of nutriment, and for many days the men had to cut branches from the trees and gather cane from the swamps to keep the horses and mules from starvation. On July 11th, Colonel Trumbull, with a portion of his regiment, had a brief skirmish with a rebel cavalry force, which made a rapid retreat. Pursuit could not be successfully made, owing to the poor condition of the horses. On July 13th, Major Drummond, with a detachment of the regiment, crossed the White River, and made a successful foraging expedition, during which he met and had a slight skirmish with a small force of the enemy, capturing a few of them with their arms and horses. He returned to camp with quite a drove of cattle, mules and horses, which he had gathered up in the country through which he passed. About the same time Colonel Trumbull, with two hundred and thirty men of his regiment, engaged in a similar expedition, in another direction, and with equally satisfactory results. He returned to Devall's Bluff on July 15th. Information having been received that a strong force of rebels was about to occupy Saint Charles,—a landing on White River, midway between its mouth and Devall's Bluff,—a brigade of troops, under command of General Lee, was hurried from Morganza, La., to Saint Charles. General Lee had about two thousand infantry, a few pieces of artillery and a gunboat, but no cavalry. To supply that want, a part of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry, under command of Major Ensign, was sent to join General Lee's command. The detachment reached Saint Charles two days after the arrival of General Lee, who had taken a strong position and was awaiting the attack of the enemy, of whose location and movements, however, he had gained no information. Major Ensign's command was at once utilized in exploring the surrounding country in search of the enemy, and, after a rapid march on July 28th, came in sight of a force of rebels on Bayou Metoe. The rebels made a hasty retreat to the south side of the Arkansas River. Major Ensign then turned to the south and east, drove in the rebel pickets near Arkansas Post, and, moving down the north branch of the river for several miles, encountered and dispersed small parties of the enemy, taking some prisoners. From the prisoners the Major obtained the information that a large force of rebels was in camp upon the opposite side of the river. He at once moved his small command from that dangerous neighborhood and, marching rapidly, reached Saint Charles on July 30th, having fully accomplished the object of the expedition. The rebel General, having learned of the occupation of Saint Charles by a Federal force amply sufficient to defend it, abandoned his plan for attacking that place and rejoined the main rebel army, under General Price. After being advised of the retirement of the rebel force, by scouting parties from Major Ensign's detachment, General Lee, leaving a sufficient force to defend the post at Saint Charles, returned with the rest of his command to Morganza. About the same time Major Ensign returned with his detachment to Devall's Bluff, taking with him many negroes, as recruits for the colored regiments, also many horses and mules which he had captured.

On the 5th of August, the Ninth Iowa Cavalry, together with the other regiments composing its brigade, moved northward to take part in a cavalry expedition, commanded by Brigadier General Joseph R. West, which it joined near Searcy. The entire force, numbering nearly 3,000 men, crossed the Little Red River at Searcy, and moved to a point on White River, above Augusta. The rebel General Shelby's force numbered about 6,000 men, but, as he had detached about one-half his men on an expedition against Helena, it was General West's purpose to meet him before his command could be reunited. It had been arranged to have transports sent to Augusta, to ferry the troops across White River. The boats failed to come, and General West was obliged to get his cavalry across the river by swimming. So much time was consumed that, before one-half the troops had crossed the river, news was received that the rebel force sent to Helena had rejoined General Shelby. The discrepancy in numbers was too great to justify General West in risking a general engagement in the open field. He therefore decided to fall back to the defenses at Devall's Bluff and Little Rock. The retreat was successfully accomplished. General Shelby followed in pursuit, and there was some skirmishing with his advance guard, but the troops safely reached their strongly fortified encampments, which the rebel General had the good judgment to refrain from attacking. The condition of the horses at this time was very poor. They had been greatly overworked in the long scouts which had been made, had not been supplied with a sufficiency of forage, and there were not enough really serviceable horses in the whole brigade to properly mount one regiment.

On the 24th of August, the rebel General Shelby, who had pursued a detachment sent out from Devall's Bluff on a scouting expedition and followed it almost to the line of defenses, succeeded in surprising a party of soldiers belonging to the post, who were making hay on the prairie near Ashley Station, and, after a very stubborn resistance, captured part of them, dispersed the balance and burned the hay. As soon as the men who had managed to escape reached the post, all the men who could be mounted on serviceable horses, numbering 750, under the command of Colonel Geiger of the Eighth Missouri, started in pursuit of the rebel force, which was encountered on the open prairie. The rebel force outnumbered that of Colonel Geiger in the proportion of three to one, but the Colonel resolved to make the attack. He disposed of his force in such manner as to avoid being surrounded and cut off from retreat. The Ninth Iowa was placed in position to guard the line of retreat, in case it became necessary, and was not engaged in the heaviest of the fighting which ensued, but it bravely performed its duty in the position to which it was assigned. The Missouri regiments, led by Colonel Geiger, boldly charged the enemy, who gave way, under the impression that the attacking party was merely the advance of a larger force. The rebels lost heavily in killed and wounded, their loss being much greater than that of the Union troops, owing to the impetuosity with which the attack was made, and to the superior quality of the arms of the attacking force. The loss in Colonel Geiger's command, in killed and wounded, was sixty. No prisoners were taken by either side. The loss of the Ninth Iowa, on account of the position to which it was assigned, was small, as compared with that of the regiments which led the advance and charged the rebel line. The rebel force retreated under cover of the darkness, which came on soon after the fighting began. Colonel Geiger, and all the troops under his command, received high official commendation for their admirable conduct in this spirited cavalry engagement.

On August 27th, Colonel Trumbull marched with most of his regiment upon another cavalry expedition. He joined other troops from Little Rock, and the expedition, under command of General West, made a long and arduous march through the rough and broken country lying between the Little Red and White Rivers. The expedition encountered no considerable bodies of the enemy. Upon its return, the brigade, consisting of the Ninth Iowa and the Eighth and Eleventh Missouri, was halted at Austin, where it went into camp. Sixty men of the Ninth Iowa, with Captain Young and Lieutenant Holmes, who had been left at Devall's Bluff, embarked on a transport take the expedition but, meeting with a largely superior force of the enemy, for Clarendon, September 1st. They were instructed to scout the country between Clarendon and the Arkansas River, and to then return to Devall's Bluff by land, which duty was successfully accomplished. A small detachment of twenty men of the Ninth Iowa was sent to act as scouts for a force of infantry, which it accompanied upon a transport up the White River. These troops had orders to co-operate with those under the command of General West, whom they were to meet at a designated point on the river. Not meeting General West's troops, at the point indicated, the scouts from the Ninth Iowa were ordered to disembark and make the effort to communicate with the General. The little detachment made a heroic attempt to overtake the expedition but, meeting with a largely superior force of the enemy, was overpowered, and, after a desperate resistance, nearly all the men were either killed or captured. It was in the performance of such hazardous scouting duty that most of the casualties of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry were sustained. It required a high degree of courage and fortitude, on the part of the men composing these small scouting parties, to ride along the lonely forest roads, not knowing at what moment they would be attacked by the enemy concealed in ambush. The character of the service was much the same as that which was required in the early history of the country, in fighting Indians, and the fate of those who fell into the hands of the rebels was about as much to be dreaded as that which befell the prisoners in the hands of savages. While there were exceptional cases, in which Union prisoners received humane treatment, it is a well known fact of history that, as a rule, their treatment was marked with great inhumanity.

On the 8th of September, that portion of the brigade which had been stationed at Devall's Bluff—including the Ninth Iowa was ordered to move to Austin and join the main command. About this time the rebel General Price had concentrated his army and had commenced his last great campaign, extending his operations into the states of Missouri and Kansas, where, in a series of hard fought battles, his army was defeated with heavy loss and compelled to retreat into the mountains of Arkansas. An expedition, composed of one division of cavalry and one of infantry, marched from Memphis to join in the pursuit of Price's army.

On September 18th, the expedition passed through Austin on its march to the Missouri border. For the purpose of bringing back his supply train, General Mower—the officer in command—requested a detail of troops from the post at Austin, and Major Ensign, with 226 men of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry, was assigned to that duty. The detachment proceeded with the command of General Mower to the crossing of White River and, from that point, returned with the long train of unloaded wagons to Brownsville Station. The return march over the mountain roads was difficult and dangerous, but, by making long and rapid marches, the railroad was reached on September 25th, without losing any of the wagons and without any casualties in the command. In the meantime the brigade had been moved to Brownsville, from which point all supplies were received and forwarded. Quarters for the men and stables for the horses were constructed, much of the material for that purpose being obtained by the tearing down of abandoned houses and public buildings. Comfortable winter quarters were thus secured for the soldiers and their horses, but, as will be seen from the operations that were carried on during the winter, comparatively few of the men remained to occupy these quarters.

On October 30th, a forage train, guarded by a detachment from the Ninth Iowa, was attacked by a force of rebels, and two teamsters were mortally wounded and four captured. Those who escaped brought the news to camp, and a detachment from the regiment was immediately sent to the place where the attack was made. In the meantime, however, a detachment from the Eleventh Missouri, returning from a scout, had heard the firing and hastened to the rescue. The rebels were forced to abandon most of their plunder. The detachment from the Ninth Iowa did not reach the scene of conflict until the rebels were in full retreat, and, as night had fallen, could accomplish nothing beyond returning to camp with the wounded men and rescued property. At daylight Major Ensign, in command of a detachment from his regiment, went in pursuit of the rebels, but did not succeed in overtaking them.

Early in November fragments of the rebel General Price's defeated and demoralized army were retreating toward the mountains, and that portion of the Ninth Iowa, and the other cavalry troops then at Brownsville, started in pursuit on November 4th. The line of march was through Peach Orchard Gap, El Paso and Springfield, and on to Norristown and Dardanelle. On November 16th, Major Drummond, with three hundred men of his regiment, scouted the country south of the river. Major Drummond's detachment and others, moving in different directions, encountered straggling parties of Price's retreating army and captured many of them, without any serious engagements. The troops which had been engaged in the pursuit returned to Brownsville, reaching that place on the night of November 18th.

A few days previous to the starting of this last expedition Lieutenant Colonel John P. Knight, of the Ninth Iowa, with five hundred men of the brigade, had commenced a march to Fort Smith, escorting thither Major General F. J. Herron. Their route lay near the line of march of General Price's retreating rebel army, with portions of which Lieutenant Colonel Knight's detachment had several skirmishes, in one of which a rebel officer was killed and a number of his men captured, together with one hundred and thirty head of cattle which they were driving. Lieutenant Colonel Knight returned with his detachment to Brownsville on the 26th of November, having marched over five hundred miles. General Herron subsequently wrote a letter in which he acknowledged the very efficient service of the detachment and its commander.

During the remainder of November, Major Drummond, with two hundred men of the regiment and a part of the Eighth Missouri, performed very important service in guarding some government transports which had grounded at low water in the Arkansas River above Lewisburg. The Major remained upon this duty, and scouting in the surrounding country with portions of his detachment, until the close of December, when, with the rise in the river, the transports were enabled to proceed upon their course, and the troops rejoined the brigade at Brownsville.

On December 6th, Lieutenant Harmon of Company E, being in command of fifty men of the regiment, encountered a superior force of the rebel leader Rayburn's troops near Brownsville. Lieutenant Harmon's detachment had two men wounded and several horses killed. The rebels sustained a much heavier loss.

Early in January, 1865, about 1,000 men of the brigade, under command of Colonel Geiger, began a march through the region of country lying between Brownsville and Memphis, Tenn., for the purpose of dispersing such forces of the enemy as might still be found infesting that section of the country and destroying their means of subsistence. The portion of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry which accompanied the expedition was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Knight. The men and officers endured great hardship and suffering upon this march. During the previous month very heavy rains had fallen and the roads were in many places under water. The rains

continued during the greater portion of the march. Major Ensign says: "On one day we only made six miles and, when that night we reached a point between the Little Red and White Rivers, could not find enough dry land for a camping place. Passing the night there, and by dint of hard work keeping the animals and wagons from miring down in the mud and water, and throwing away tents and other camp equipage to lighten the train, we resumed the march the next morning in the midst of a snow storm. Thus, fighting the elements, we arrived at Augusta January 11th, having been ferried over White River by the steamer Belle Peoria." The weather cleared somewhat, the march was resumed, and the object of the expedition successfully accomplished. Detachments from the command were sent out in different directions, small bodies of the enemy were encountered and dispersed, and quite a number of rebels were captured, together with many horses and mules. The command reached Brownsville on January 28th. On the day before, with a small detachment, Major Ensign had marched from Searcy to Brownsville, in advance of the main command, and, when near Austin, had captured two noted bushwhackers, with their horses, arms and equipments; the Major and Adjutant Wayne had rendered valuable assistance to Lieutenant Colonel Knight during this long and, in some respects, most memorable March in which any portion of the regiment had been engaged.

During the remainder of the winter of 1865 there was the usual amount of scouting, but no incident of special importance occurred, except the daring attempt of Major Ensign and a small detachment of the Ninth Iowa to secure the capture of the notorious guerrilla chief, Rayburn. This man had given incessant annoyance to the Union troops, and General Steele had offered a large reward for his death or capture. A few soldiers from the Union army, who had been guilty of committing acts of pillage in the neighboring country, for which they had subjected themselves to severe punishment, and which they knew would be received when their crimes were discovered, gave themselves over to a course of complete outlawry, by deserting and joining the band of the guerrilla leader. The capture of these deserters was a matter of equal importance to that of capturing Rayburn and his band. Major Ensign led his detachment through devious paths of the woods and mountains, marching mostly at night, until they reached the neighborhood of Rayburn's camp, without discovery. Concealing themselves in ambush near a bridge, they kept a close watch for the approach of the rebels. On the night of April 2d, they succeeded in quietly capturing a couple of prisoners, and, from them, learned that Rayburn had himself made prisoners of the deserters, not daring to trust them as members of his band, and had sent word to General Steele that he would return them to him, if he could be allowed the necessary facilities for doing so, without taking too great risk of the capture of himself or his band of followers. The Major also learned that Rayburn had left his camp and retreated still farther into the mountains, and that any further effort to secure his capture at that time would prove futile, for the reason that he felt assured that the rebels had become apprised of his approach. It then became a matter of concern to avoid being ambushed on the return march. By celerity of movement and another all night march the detachment reached Brownsville, after an absence of eight days and nights. The subsequent fate of the guerrilla chief and his followers and that of the deserters is not revealed by the record.

The news of the fall of Richmond and the surrender of Lee's army reached the camp at Brownsville on April 11, 1865, and was fully confirmed the next day, causing great rejoicing. Then came the news of the assassination of President Lincoln. The soldiers were at first almost wild in their indignation and desire for vengeance, and it required the exercise of the strongest military discipline to prevent an attack upon the military prison at Little Rock, where rebel prisoners were confined, it having been reported that some of them had expressed satisfaction upon hearing of the death of that great and good man.

The remainder of the history of the operations of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry is soon told.

While the war was practically over, the conditions in those states which had been most active in the rebellion against the government was such as to render military occupation necessary for a considerable length of time. In those states the functions of civil government had been almost completely paralyzed during the progress of the war, and the lawless element in every community could only be restrained by the presence of Federal troops. There was, perhaps, no section of the South where lawlessness and disregard for human life was more prevalent than in the mountainous regions of Arkansas, where roving bands of outlaws were still numerous. While it was obvious that a sufficient number of troops would have to be retained in the service to assist the state and local authorities in regaining control, the volunteer soldiers felt that their duties should have ended with the putting down of the rebellion against the general government. Both officers and men felt that it was the duty of the government to increase the strength of the Regular Army, so that they might be relieved and allowed to return to their homes. hile they were given the assurance that this would be done as soon as possible, the men were impatient, and a spirit of insubordination was manifested on the part of some of them. Quite a number of desertions had occurred. The necessity for the strictest enforcement of discipline became apparent, and the officers and the better element among the enlisted men asserted themselves so effectually that the former good discipline was soon restored. This feeling of discontent was not more prominent in the Ninth Iowa Cavalry than in any of the other regiments from Iowa. It was quite general at that time, but never reached a critical stage. The men soon came to appreciate the necessity of the situation and settled into a feeling of patient waiting for the time when their services would be no longer required and they would be honorably discharged.

On June 11th, the regiment marched from Brownsville to Lewisburg. About one-half the companies were sent to garrison different posts, while the other half were retained at Lewisburg. Colonel Trumbull, who had been promoted to Brevet Brigadier General, was in command of the post, and Lieutenant Colonel Knight succeeded to the command of the regiment. Major Wayne, who had been promoted from Adjutant, was on detached duty at Dardanelle, and Major Ensign had been assigned to duty as Acting Assistant Inspector General, at Little Rock. Subsequently General Trumbull was assigned to the command of the more important post at Fort Smith, and a general change was made in the assignments of the captains and their companies to different stations.

In September, Major Ensign, acting under instructions from the Department Commander, visited the southeastern counties of Arkansas, to ascertain the progress made towards the reorganization of civil government, and to see if it were necessary for the military to afford the civil authorities additional facilities to aid in the performance of their duties. Returning from the trip On the 2d of October, he submitted his official report, after which he tendered his resignation, which was accepted on October 22d, and he was honorably discharged from the service. Major Drummond had resigned in June and received an honorable discharge. These officers were both held in the highest esteem by their brother officers and by the men of the regiment, and much regret was shown when they took their departure. Lieutenant Cheney, Quartermaster, and Lieutenant Tilford Commissary, of the regiment, are mentioned in the record for the very efficient manner in which they performed their duty, in procuring the necessary supplies for the command, sometimes under very difficult circumstances. The surgeons and company officers are also generally commended for the faithful and efficient discharge of their duties. There were numerous changes in the field and staff and in the company organizations during the term of service of the regiment, all of which will be found noted in the subjoined roster.

In January, 1866, a detachment of the regiment was sent through the Indian Territory to Texas, for the purpose of guarding a train of government wagons, loaded with supplies for the troops retained on duty in that state. The detachment was absent several weeks on this duty. During the remainder of their service, the different companies of the regiment rendered important service at their respective stations, in sustaining the officers of the civil government, both Federal and State, in the enforcement of law and order. They succeeded in hunting down, killing and capturing nearly all the outlaws and desperadoes who had infested the country and, when the time came for their departure, the conditions were so greatly improved that life and property were probably as well protected as before the commencement of the war.

On February 16, 1866, Brevet Major General H. J. Hunt, in command of the Frontier District, Department of Arkansas, issued from his headquarters at Fort Smith an order directing the relief from duty of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry, by the Third United States Cavalry, after which the regiment was ordered to proceed to Little Rock, Ark., to be mustered out of service.

The following commendatory paragraph is quoted from the order:

The General commanding takes this occasion to convey to Brevet Brigadier General Trumbull, and the officers and men of his regiment, his appreciation of the good service they have rendered while under his command, and the excellence of their discipline, which was frequently elicited the commendations of the citizens of the district. To the commanders of detached posts, Captains Reed, at Clarksville, Flick, at Fayetteville, and Lambert (specially) at Van Buren, his thanks are due for the manner in which they performed their duties—where they often had to act upon their own judgment.

General Trumbull, who was still on duty as Post Commander at Fort Smith, when his regiment was ordered to assemble at Little Rock to be mustered out, sent a farewell letter, which was read to the regiment on parade. The letter is here quoted as follows:

HEADQUARTERS NINTH IOWA CAVALRY VOLUNTEERS, FORT SMITH. ARK., FEB 19, 1866.

TO THE OFFICERS AND SOLDIERS OF THE NINTH IOWA CAVALRY:

Gentlemen: We are about to separate. Our work is done. The flag of the Republic waves triumphantly over all her ancient domain. In the great struggle which has passed, you have done well, and you leave the service carrying with you a noble tribute of approbation from the Major General commanding the district, one of the greatest soldiers of the country. The hardships and dangers you have undergone have been great, and many of our comrades have sunk by the wayside. The discipline has been severe but it was necessary to make soldiers of you. In the new positions you are to assume, preserve your soldiers' name untainted, and, should the President of the United States again order the long roll beaten. I trust we shall all be ready to fall in. May prosperity and happiness attend you all. Comrades, I bid you farewell.

M. M. TRUMBULL, Colonel

Ninth Iowa Cavalry Volunteers and Brevet Brigadier General U. S. V.

The companies of the regiment were all mustered out of the service of the United States at the city of Little Rock, Ark., but upon different dates. Companies E. F. G. H. K. L and M were mustered out on February 3, 1866; the field and staff officers and Companies A. C and D were mustered out February 28, 1866; Company I was mustered out March 15, 1866; and Company B was mustered out March 23, 1866. All officers and enlisted men, not otherwise accounted for, were mustered out as with their respective organizations. It will thus be seen that a period of nearly two years and four months had elapsed between the muster in of the regiment and the muster out of its last company.

During its service in the South the regiment marched over 2,000 miles, was conveyed by steamboat and rail 1700 miles, and the marches of its various detachments approximated 8,000 miles. The casualties sustained by the regiment—killed in action, died from the effects of wounds and from disease, discharged for disability incurred from wounds or sickness, including transfers—number 309 Enlisted men and officers. The survivors of the Ninth Iowa Cavalry may well be proud of the record made by their regiment. While the field to which its operations were confined was not the scene of any of the great battles of the war, in which so many of the regiments from Iowa participated with distinguished honor to themselves and their State, yet the Ninth Cavalry faithfully performed all the duties to which it was assigned. Its officers and men had bravely met and fought the enemy in minor engagements, and they would have gladly welcomed an order—for which they waited in vain—to participate in the great battles which marked the closing campaigns of the war. The regiment is, therefore, justly entitled to as honorable a place in the military history of its State as that of any of the long line of Iowa regiments which went forth at the call of the President of the United States and contributed so largely to the salvation and perpetuation of the best government ever instituted among men. The record from which the last quotations are made can be found on page 563.

Report of Adjutant General of Iowa, 1867, Vol. 2.

Report of Adjutant General of Iowa, 1867, Vol. 1, page 46.

[table]

SUMMARY OF CASUALTIES

Total Enrollment .............................1353

Killed .............................................................9

Wounded ......................................................15

Died of wounds ........................................10

Died of disease ......................................165

Discharged for wounds, disease or other causes...89

Buried in National Cemeteries ........100

Captured ......................................................10

Transferred ................................................11

NINTH REGIMENT IOWA VOLUNTEER CAVALRY

Term of service three years.

Mustered into the service of the United States at Davenport, Iowa, November 30, 1863, by Lieutenant Colonel William N. Grier, United States Army.

Mustered out of service on dates ranging from February 3, to March 23, 1866, at Little Rock, Ark.

COMPANY "H"

Gardner, Wayne H. Age 18. Residence Dayton, nativity Illinois. Enlisted Oct. 24, 1863. Mustered Oct. 24, 1863. Mustered out Feb. 3, 1866, Little Rock, Ark.

Garrett, Charles R. Age 21. Residence Hopeville, nativity Illinois. Enlisted Aug. 22, 1863. Mustered Aug. 22, 1863. Mustered out Feb. 3, 1866, Little Rock, Ark. See Company B, Eighteenth Infantry.